The project brings different groups of Israelis and Palestinians together, to learn about the personal and national narrative of the “other”

The learning experience in the meetings is based on a combination of historical national information and the personal and familial stories of the participants

All people are born with desires, aspirations and wishes they seek to achieve. But, in societies that live in ongoing conflict, these wishes and aspirations are very much determined by the narrative of the community a person is born into. The community’s story, its perceptions and beliefs, all greatly determine a person’s position and role.

We perceive the narratives we are born into as the truth, and many factors are at play to keep each side only recognizing its own story and tragedies. The physical and emotional distance between the two conflicted communities doesn’t allow either side to hear its counterpart and thus the sides don’t meet or recognize one another.

It is from this perspective that the PCFF initiated the Narratives project. Through this project, we don’t seek to cancel or approve any specific narrative, but rather to create a journey through the personal and national history of each side, through meaningful dialogue, respect and understanding that each personal and national narrative holds a truth in it.

Since 2010, the PCFF Parallel Narrative Experience brings together groups of 15 Israelis and 15 Palestinians (and 12 Israelis and 12 Palestinians on Zoom during Corona time) for a module with unilateral and bilateral workshops and dialogue activities in order to learn about the personal and national narrative of the “other”, as an important step towards reconciliation between the peoples. We had about 45 groups until today.

A visit in Kfar Lifta – the youth group of the Narrative Project

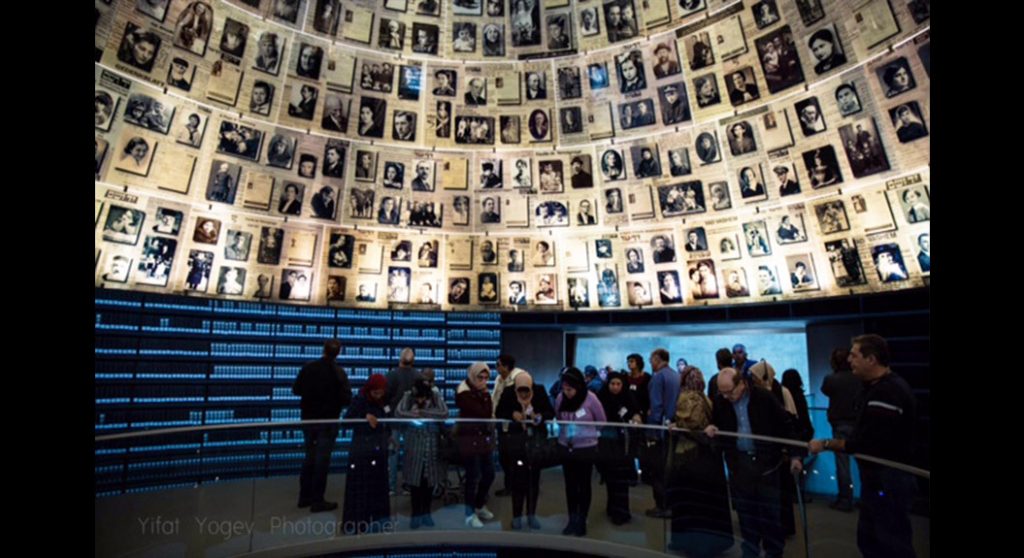

This PNE focuses on reconciliation on the interpersonal levels where individuals deal with changing attitudes, recognizing the past and current situation. They do this by interpreting their personal and historical narratives, and the personal and historical narrative of the other as part of, or a complement to, the larger public and national narrative. The project uses sites such as “Yad Vashem” museum to learn about the Holocaust and the village Lifta which was destroyed in 1948, to learn about the Palestinian Nakba, as a way to provide a concrete context to illustrate the interpretation of historical, personal and national narratives from both sides and the complexity of the conflict.

Despite the charged subjects, the facilitators, who are bereaved PCFF members, make sure they provide a safe space that allows all the participants to take part in an empathic and inclusive dialogue. Participants are exposed to the messages of dialogue and reconciliation as promoted by the PCFF, and understand the importance of recognizing the “other”. When these meetings end, project graduates (alumni) are invited to take an active part in the alumni community, and to join the work and activities for advancing reconciliation between the peoples.

Palestinians and Israelis complete the program with a new understanding of the conflict and of the other side, with a belief that reconciliation is possible, and with a desire to keep in touch with each other and to work together to promote a change in the harsh reality of the conflict. This alumni body is a vital resource, not only for the PCFF, but also for a more vibrant civil society. In 2017, it was decided to recognize all the PNE alumni as a single community, and establish a framework of activities for this community which currently includes more than 1,200 people.

The PNE-based projects have been predominantly funded from the get go by USAID and the EU.

Project alumni share their stories

Haled Juma

My name is Haled Juma, I’m a high school guidance counselor in Palestine and I live in the al-Arroub refugee camp outside Hebron. I took part in the Narrative Project comprised of individuals in the mental health field.

The Narrative Project was a profound experience for me since I never thought I’d sit in Palestine with a group of Israeli Jews willing to listen and discuss the rights of the Palestinian people. I was pleasantly surprised by the Israelis’ empathy when the Palestinians shared their personal stories and harsh experiences at the hand of the Occupation soldiers.

During the seminar we went on two tours to learn about the national narrative of both sides. The first was to the village of Lifta whose residents were driven out in 1948. The tour to the village evoked deep sadness in me and brought to mind the descriptions and stories that my father used to convey about his village, Hatta.

The second tour was to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. This center depicts the Nazis’ crimes against the Jews during WWII. What I saw on the tour saddened me very much and the photos and descriptions pained us, the participants, very profoundly.

I had hoped and expected of the Jews, who now have power and influence, not to repeat the acts of discrimination and oppression towards powerless people. A question I ask myself, to no avail, is how a people who endured such oppression, torture, discrimination and racism can discriminate and oppress another?

During the encounters I met a group of Israelis and formed ties that last to this day. I discovered people who have true empathy and who support our right to live free in an independent state, not under occupation. The visits we group members made together made me very hopeful that there is a true opportunity for co-existence if only people would get together, face to face, and speak from the heart.

Ziva Rahamim

My name is Ziva Rahamim and I live in Or Yehuda.

When I came upon the ad for the Narrative Project I decided to sign up and take part. “From not for its sake, comes for its sake”, since I never really delved into the intricacies of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I always felt that the conflict was too complex for me to take a stand or engage in the matter myself.

When I was informed I was accepted into the Narrative Project I apologized and said I have no idea how to solve the conflict but I am willing to listen and study.

As early as the first encounter with the Palestinian women, I could instantly relate to their loss, sadness and distress. At the end of the sessions, I realized that I can better understand and gradually wartime situations that I experienced as a child came to mind, situations that I had repressed and that had faded from memory as years went by. I recalled the Six Day War when I was forced to run into the trenches when the siren sounded; I remembered how the emotional stress rattled my physical wellbeing, the fever rose and exhaustion overpowered fear. I recalled how during the Yom Kippur War, while my father and three brothers were mobilized, I heard my mother say she can’t fall asleep at night and must take a sedative. I remembered I was so afraid for my three brothers fighting in their tanks that I went out to the balcony and asked God to bring them back wounded at most. I remembered how I felt when I got word that one of my brothers was wounded and lost his eye and I also remembered how everything changed after that, when my parents were focused on my brother’s recovery and I was forgotten in the mix. As a result of these memories I concluded that we mustn’t wait for peace to be made between the leaders on our side and theirs; a basic peace between us women on both sides will take us a step further towards the global solution. Our compassion, sensitivity and sisterhood is invaluable. I call for more and more women to join because only we can.

Eran Ram

My name is Eran Ram. Ram in Hebrew is an animal, but it’s also the initials of Rabbi Aharon Moshe, a great rabbi in Galicia (a region between Central and Eastern Europe). Some of my relatives died in the Holocaust, but my grandfather and grandmothers fled before the war. My family are Zionists through and through. One grandfather was among the founders of the “Dan” cooperative and my other grandfather was head of the Jezreel Valley Council for many years. My grandfather fought in the War of Independence and my father later fought in all the wars. My father was wounded twice during his military service and my sister was wounded by an explosive during a trip. I served in the army as a company commander. Today I am married with three children and I’m a high school teacher.

My entire life I was politically involved. I always knew that we belong here, yet, we are not alone. I served often in the Territories but I never really knew the Palestinians. I had this burning desire to sit down, to talk, to listen and perhaps even to create a dialogue with the other side, so I joined the Forum’s Narrative Project.

I attended the sessions with concern and hope. The first session I sat down outside the circle, observing and examining as I do. At one point a young Palestinian sat down beside me; I looked at him, smiled and said: “Hello, my name is Eran, you look tired”. “Yes,” he replied, “My name is Tarek, I’m from Bethlehem and I worked until late last night”. I suddenly realized how complex it is and how easy it could be.

The sessions were eye-opening, rattling, rough, depressing and hopeful at the same time. At one of the advanced sessions I talked about my service as an officer in the Territories, especially in Hebron, and for a surreal moment we tried to recall if we met in the past, at a checkpoint, me as a soldier and them on the other side of the fence. It’s hard to view someone as an enemy when you talk as equals. We didn’t try to reach any final or mid-term resolution or decide what is just and who is right, but we did try to see and understand reality from the eyes of the other side.

What’s great about the sessions is the ability to have a discussion and listen, but I deem the main success the small moments of intimacy and trust that are created in the one on one encounters. The sense that in this ocean of hate and ignorance there are islands of hope, that we are holding out for hope and the future. With the support and encouragement of the Forum, a small group of Israelis and Palestinians got together and initiated a project that will allow families and individuals on both sides to get to know one another in the hopes that they will experience, even in the slightest, what we experienced in the sessions.

I am sitting at my computer in this chaos the country is enduring, sitting and worrying. Worrying for the future, for my family, for Israelis, for Palestinians and for my friend Tarek from Bethlehem.

Siham Abu Aram

My name is Siham Abu Aram. I live in Yatta in the Hebron Governorate and I took part in the Narrative Project with individuals from the liberal professions. The sessions were new to me and foreign.

Before I started attending, there were many emotional barriers between myself and the Israeli people.

I listened to the Israelis and they listened to me. We shared our pain and hope. We laughed and cried together.

When the group visited the depopulated village of Lifta and discussed the Palestinian Nakba, I experienced this terror and pain as a result of the ongoing

Occupation of the Palestinian people of who I am one.

During the tour, that lasted over three hours, I looked at my Israeli partners; I saw to what extent they’re hurting the pain of what happened to the village locals, the uprooting and the killing. And this is one of hundreds of villages that were depopulated in 1948.

When we visited the Yad Vashem Museum in Jerusalem and listened to the Israeli narrative, I sensed the extent of suffering the Jewish people endured at the hands of the Nazis, which we Palestinians are not to blame for.

Both sides shared the sorrow and in the joint sessions after those tours the discussion was extremely piercing, yet a must to get to know the other’s story.

This experience gave me hope for a better future between both nations. The discussion is what’s been lacking. The need to know the other. The PCFF provided us the opportunity to create ties and discuss our day to day in the shadow of the ongoing conflict and the Occupation that we hope will be eliminated quickly so we can live in peace, side by side.

Fauzi Switi

My name is Fauzi Switi. I live in Dura, in the Hebron Governorate. I have a BA in Arabic Literature.

It’s not easy to talk about the attempt to make a change in a person’s life. It’s not easy to change the image etched in memory for decades, an image that is supported and affirmed by events on site. It’s not easy to sit with the side defined as the enemy in your memory and thoughts. I was raised to believe that the Israeli is the enemy that uses force, that he’s a murderer and a criminal. That he’s the source of all our troubles, whether he took part or not.

I myself suffered from the wrongs and the oppression of the Occupation. I was arrested several times and each time I suffered pain, torture, humiliation and my freedom was taken away.

Harsh experiences are still etched in my memory from the images of the arrest, from my home to the interrogation, the cell, the prison and the military courts where there is no mercy or law.

All these events resulted in a portrait of Israelis who are criminals and murderers. But I had the privilege of being present at the Forum’s Narrative Project. These sessions were attended by an equal number of Palestinians and Israelis and a discussion took place on many subjects. I discovered that the Israeli has a narrative whereby he’s convinced he has the right, he’s a victim and he’s protecting his right to live.

Then there were us Palestinians who talked about being robbed of our lands and the victims of Israeli violence and crime.

After many discussions I reached several conclusions:

- The session and the confrontation with the other side are necessary.

- The narratives and communication between the sides depict a different picture whereby people want to live, they want peace and security. A picture whereby people are hurting the loss of their loved ones in this conflict that has been ongoing for decades.

- The encounter with the other side makes you see the man and his humanity. This image was lost behind the images of violence and hate.

When you hear the discussion about pain, suffering and hope you feel as if the speakers are one person, despite the different language and opinions. The encounter reinforced this notion in me of accepting the other and though we think differently, we have in common our humaneness in all its aspects.

I believe that meeting the other and listening to what each other has to say about the pain creates the ability to change. These sessions transformed past enemies into friends who endeavor together against the Occupation and take part in activities that serve the Palestinians.

In conclusion, behind the negative stigma related to the other there is an invisible image of pain and suffering that got lost in the conflict. The sessions prove that it’s important to focus on the human aspect of the conflict in order to turns enemies into friends who stand together, who cry out for freedom and justice for those who were wronged.

And one last thing – what we envision based on what we hear is a false image, the image of the battlefield hides the human aspect of the other side.

Alon Simon

My name is Alon Simon. I’m 34 years old, originally from Kibbutz Nitzanim, and now live in Tel Aviv.

Last year I participated in the Narrative Project – a series of meetings in Beit Jala organised by The Parents Circle – Families Forum. The purpose of the project is to bring Israelis and Palestinians together to share and understand each others’ personal and national narratives.

I experienced meeting with the Palestinians in the group in two different ways.

During breaks from the organised discussion groups and seminars, I met very hospitable, smiling people.

They shared with me pictures of their families and homes, told me how much they wanted peace, and their belief that all people are equal. Above all they dreamed of a normal life – of working for a living, caring for their family, taking a vacation without fear or worry, and without the constant threat of roadblocks and curfews.

The meeting that took place in the organised discussion groups was completely different. The atmosphere was of Israelis opposing Palestinians, of nation against nation.

From the first discussion group the Palestinians were enraged with us, the Israelis. It made no difference that the Israeli participants were all people who wanted to see an end to the occupation. In the discussion groups we were representatives of all Israelis from all generations.

Many of the Palestinians had stories about violence they had experienced at the hands of the army and security services. They spoke of how they had been detained, interrogated, beaten and humiliated. We Israelis heard the stories and didn’t know how to react. I did not know what to say. What could I say? I am on the stronger side, free to go where I choose, and have never been humiliated or abused by the authorities.

The feelings in the Israeli group ranged from empathy and guilt to anger and frustration. We were angry that the Palestinians could represent themselves as an entirely innocent people and Islam as a religion of peace when from among them come horrific acts of terrorism. We were frustrated by the lack of balance in the discussion. One side spoke of its suffering and accusations and the other was expected to listen and accept it in silence.

To the anger of the individual Palestinian’s experience was then added the anger and humiliation of the national Palestinian experience of the nakba.

Our group took a tour to Lifta, a village at the Western edge of Jerusalem that has been abandoned since the 1948 war. According to our guide, the Israeli state had done everything it could to clear the Palestinian residents from its territories, using violence and intimidation. After the war the Palestinians who fled were not allowed to settle back in their homes, which became Israeli settlements.

The trip shook my beliefs and perceptions. I had always seen Jewish settlement of the land inside the borders of Israel as just, and the Israeli settlements in the West Bank, on the other side of the Green Line, as immoral. But after my experience at Lifta, the whole morality of the state of Israel has been thrown into doubt. It forced me to question the country where I was born and grew up, and that my grandfathers fought to establish.

Now that I am conscious of the nakba, should I believe that Petah Tikva, the first Jewish settlement in Israel, is no different than the outposts in the West Bank, as one Palestinian participant claimed? Are the contemporary settlers of the West Bank the new Zionists – as they claim – equivalent to the Zionists that established the state? I still cannot accept these conclusions, and I’m still looking for arguments strong enough to reject them.

So what can I say? It’s clear to me that the reality is far less black and white than is often portrayed. Most people – including leftists and humanists – tend to stick to their own reality and close their ears to conflicting opinions. They fear that if they listen to other perspectives their own truth will bend and crack, and even lead to complete acceptance of the opposing view. It’s difficult to concede that there can be elements of truth in both narratives. If I took anything from these meetings, it’s the determination to overcome this instinct and to truly listen to the person facing me with an open mind.

I recently read an article about whether it was good to use the term ‘Palestinian’ in Israel. The article quoted Menachem Begin, saying “If this is the Land of Israel, we have returned to it. If it is Palestine, we have invaded it. If it is the state of Israel, we have established legitimate rule throughout it; if it is Palestine, our rule is not legitimate in any area of it.” I want to get away from Begin’s conception, Israel or Palestine. I want Israelis to accept the Palestinians and their suffering and needs, as I wish they would recognise us, with our suffering and our needs. I want each side to loosen its grip over their national narrative.

The Palestinians are people just like us. Before the meetings, I had the impression that they had the moral high ground because they were under occupation. Now I think less like this. They have corruption, racism, violence and provocation – just as we do.

But to finish on an optimistic note, I genuinely feel after these meetings that I have someone to talk to on the other side. I won’t always like what they have to say, and I don’t think we’ll agree about everything, but I know there are Palestinian partners with which we can create a new reality – a reality of two states living side by side.

Muhammad Abu Snina

My name is Muhammad Abu Snina, I live in the Old City of Hebron. I am a security guard at the local bank and I attended the Narrative Project’s “We want a better future” group.

I very much wanted to take part in the project for several reasons: I wanted to hear the narrative of the Israeli side and I wanted to tell my story and discuss it up close, as each side listens to the narrative of the other.

Initially, we weren’t optimistic. When we shared our personal stories and our suffering under the Occupation, some were very compassionate, some couldn’t accept what we were saying and left the project, some remained, yet stood by their opinions zealously.

The project included several field trips.

One was to the Palestinian village of Lifta that was depopulated in 1948 by Zionist groups. The Israelis empathized with us when they saw the village that was uprooted and not a resident remained because it was clear they were all forced to leave their homes whether they liked it or not.

We visited Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. We learned how the Jews were treated in Europe, especially by the Nazis. During the visit we felt sorrow for what we saw and we identified with the Israelis and their pain. The visit left its mark on us.

Since the main source of the Israeli people’s suffering is the Nazis and not the Palestinians, why do the Israeli government and people harass the Palestinians and treat them with racism, oppression and injustice when their goal is peace? Do we now have the power?

During the project we met Israelis and formed friendships. With some we’re in constant touch, we visit each other’s homes. Some spread the word about their experience in order to get as many people as possible to believe in peace, in life in two independent states, not under Occupation.

The visits and encounters between us and the Israelis in the project filled me with optimism in that both peoples can determine their own fate, spread hope for a better tomorrow, for co-existence and peace between the two sides.

Saal Jabarin

When my friend Adam told me about the PCFF Palestinian-Israeli Narrative project, I wondered to what extent the Israeli narrative is credible, the narrative that we Palestinians deem false and misleading.

I wondered how much I know about the Palestinian narrative and if I can convey my story in a distinct way to the other side, knowing that my participation in this group will be via ZOOM encounters.

Every Thursday for 14 weeks, each session four hours long, I said to myself that I wouldn’t see them through; I can’t sit in front of a screen for four hours straight. Yet I decided to try in order to learn more about my narrative – the Palestinian narrative that interests me more than any other.

At first, I was asked to fill out a questionnaire on my familiarity with my community, my connection thereto and my ability to understand both narratives. The questionnaire was full of questions that are personally important to me, questions I never would have asked myself, and that was exciting for me.

We began the first session with the other side, which was in fact a virtual introduction of all the participants. There were several activities that were prepared by the wonderful and unique PCFF administrative team and it was clear that they are very skilled at managing programs such as these. All the participants had CVs rich in culture and education and everyone was eager to get to know the other side.

By chance, after the first two sessions, military escalation began in Gaza and with every missile that came down on my people in Gaza I was reminded of the people on the other side and I said to myself – How can I meet with these people? The enemy that is bombing our people? How can I listen to their story and hear from them of their solidarity and to what extent they oppose the attack on Gaza?

The first encounter after the military escalation was very hard for me, knowing that everyone expressed their opposition and denounced the military escalation and how each of us, on both sides, remembers people we lost as a result of the continuing conflict; it was very sad.

We carried on with the sessions every week and I remember that most were sad and painful in terms of the experiences we heard from both sides and from respectable historians.

At every session I recalled an incident I experienced as a result of the Occupation or stories I heard from my grandparents about the Nakba or the Naksa. It’s so painful to listen to the distinct Palestinian narrative when all the stories are full of violence and pain that the Palestinian people suffered and are still suffering and it’s also very important to me to learn how to tell my story in the right context.

In any event, I couldn’t wait for Thursdays to listen and to learn more and to discover the Forum’s unique programs; to understand how useful and necessary they are to every Palestinian. Even when I heard from the historian about the Holocaust that the Jews endured in Germany under Nazi rule, I mourned deeply for the victims and their loved ones.

Fourteen sessions went by faster than I expected. At the end of each, I felt that we are just beginning and the ideas and information were etched in my mind.

During one of the sessions, each side was asked to assume the role of the other – the Palestinian assumed the Israeli role and vice versa, and each defended the other’s narrative. Though all the activities were significant, this one was the most significant to me. Each side discovered to what extent it understands and can relate to the other’s narrative and each side assumed the role of the other and defended it well.

It’s wonderful that both sides in the conflict understand one another and know the other’s narrative. If this concept were to become a common practice in both societies and people were convinced, there would be no wars or conflicts, just peace, love and brotherhood.

Gilles Alexandre

“Each of us has a name given by the Source of Life and given by our parents”

… Mason, Tzvia, Adam, Rachel, Yaakov, Rafi and more.

Every Thursday, we met for 4 hours straight on ZOOM. A virtual green line tried to separate us, but gradually the fears and partitions fell away. With facilitators Anat and Muhammad, translators Dima and Ahmed, we could listen, ask, probe and understand. Everyone became acquainted with the other’s personal and national narrative. The national narratives are so unlike one another, yet so similar in terms of what’s lacking. And once again, it seems that a nation is a mosaic of people who differ in opinions, faith and life stories. At the end of the tenth and final encounter, we want to keep in touch and meet face to face, until our leaders understand that only with true dialogue, by renouncing dreams, can both nations live side by side in peace. And I feel that I have become a better person, more understanding of the pain of the other while having reinforced my identities.

Thank you to the PCFF for allowing me to take part in the project. I highly recommend that all my friends take part in similar encounters.